Fresno Criminal Lawyer

Fresno Criminal Lawyer – Criminal Defense Lawyer Rick Horowitz

The last few days, I’ve been in Las Vegas. Yeah, I know. But it’s not all fun and games; mostly, it’s not games at all. Since I like learning, it is fun.

The idea for this post — “Orphans in Poisoned Libraries: Training LLMs (and Children) on Racist Datasets” — comes from this experience. I attended the 2025 Forensic Science seminar put on by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, of which I’ve been a member for many years now.

Fittingly, given my recent focus, I sat through the entire “AI & Technology” track in the training.

Introduction

Anyone paying attention realizes we are living in a strange, dangerous moment. Across the country, under the banner of dismantling “DEI” — an agenda pushed by the Trump Administration to distract from the pillage, plunder, and transformation of our democratic republic into an authoritarian oligarchy — government offices are purging our people, our history, and our progress.

Websites that once documented the contributions of Black Americans, Latinos, and Native peoples are being deliberately “disappeared.”

The administration is removing data sets and rewording histories.

The misnamed “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) is firing people, not because they were unqualified, but because they have become too visible. Our white nationalist government is revolting — in every sense of that word — because of their view that the United States is becoming too Black, too Brown, and too unacceptable to the New Order that demands whiteness without apology.

It’s to be expected. When regimes have sought to control the future, they have often begun by erasing the past.

The Nazis spoke of a “New Order” as they burned books, purged archives, took over university curricula, and “synchronized culture” to suit their ideology.

Today, we watch something quieter but no less dangerous: websites stripped of Black, Brown, and female histories; records erased under the banner of dismantling “DEI,” truths removed before the next generation — and the next generation of machines — can inherit them.

It would be foolish to imagine that these acts stay neatly contained.

They bleed outward. Into the stories we tell about ourselves.

Into the datasets from which future generations — including future generations of machines — will learn.

Our cultural archives — and by adding the word “cultural” I’m expanding beyond the idea of books, papers, websites, and other records to include all the structural components of our racist United States — were already poisoned. And we are now ripping out the few antidotes that remained.

And in doing so, we are making sure that when we send the next generations into the libraries, there will be even fewer honest resources for them to find. (And, oh, by the way, Trump wants to make the problem of biased, racist AI even worse.)

Orphans in Poisoned Libraries

We left orphans alone in poisoned libraries. We told them to learn everything, and then we blamed them for what they learned. LLMs like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude weren’t taught through careful curation. No one stood by to explain that some victories were built on the backs of others, or that some records preserved injustice rather than truth. Instead, we opened the doors to everything — to verdicts born of racial terror, to medical texts that mistook oppression for biology, to journalism that taught readers to fear certain faces. And when the orphans dutifully absorbed it all, we recoiled at the reflections they offered back.

(Children learn the same way. No one hands them a syllabus titled “Injustice and How to Perpetuate It,” but they study it all the same. They study it in the way a mother’s voice sharpens when she locks the car doors. They study it in the way certain names earn respect and others earn suspicion. They study it in what is said and what is unsaid. Like the orphans we have abandoned to poisoned libraries, children absorb the lessons we pretend not to teach.)

And this happens even when we take deliberate steps not to teach something, like how to disparately treat people on the basis of race.

“In a world where we have lots of information about every individual and a powerful machine to squeeze out a signal, it’s possible to reconstruct whether someone is part of a protected group even if you exclude that variable,” Spiess says. “And because the rules are so complex, it’s really hard to understand which input caused a certain decision. So it’s of limited use to forbid inputs.”

— Katia Savchuk, “Big Data and Racial Bias: Can That Ghost Be Removed from the Machine?” (October 28, 2019)

When the machines echo back our biases, it is not a sign of their failure. It is the surest sign of their success.

At least at learning what we really value.

The Inheritance of Racial Stereotypes

LLMs, in some sense like children, are trained not — or at least not only — by explicitly teaching them “rules” to live by. They are trained from texts. Large data sets of information.

We don’t know exactly how they learn to do what they do, but it’s essentially “automatic” upon exposure to “data.”

I’ll get into why I’ve used scare quotes around “automatic” and “data” in a bit. But the key point is that we essentially say, “Here, read this and see what you can learn.” We might be thinking — especially when it comes to LLMs — that we mean “about language.” But then we feed them Comparative Physiognomy, or Resemblances Between Men and Animals, by James W. Redfield, M.D. Or the works of Ernst Haeckel, who through

The History of Creation [which] was translated into all the major European languages — … played an active role in helping concepts regarding the inferiority of certain “races” to spread and have an impact.

— Bernd Brunner, “Human Forms in Nature: Ernst Haeckel’s Trip to South Asia and Its Aftermath” (September 13, 2017)

Nor are such ostensibly biological, medical, or scientific texts the only datasets that, while teaching LLMs language, also teach and bake in racial bias.

How about a nice diet of Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Civil Rights Cases (1883), Lum v. Rice (1927), or a dataset containing Jim Crow Laws (and the justification for them)? All of these, and more, reinforced “Justice” Taney’s view from Dred Scott that “so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

Think that’s enough? What about journalism? As we know, AI is trained on large datasets of news, lifestyle, and other journalistic articles.

Yet journalism — especially historically — criminalized Black and Brown bodies by consistently portraying people of color as inherently dangerous, threatening, or lawless, regardless of individual guilt or innocence. It wasn’t just what stories were told, but how they were told, whose voices were amplified, and what narratives were normalized.

Just think back to the not-that-long-ago controversial move of darkening O.J. Simpson’s face on the cover of Time Magazine.

If we fail to consider the entire communicative ecology in which LLMs grow up, or

If we focus on one particular kind of media at the exclusion of others, if we do not look at the entire communications ecology and how it affects other pieces of how local communities get their information, then we are missing the forest for the trees[.]

— University of Southern California Professor Mark Lloyd, quoted in Joseph Torres, “Diagnosing the History of Racism in the Media” (October 13, 2022)

All these (and, as I have said, more) comprise the poisoned libraries we feed all we create, including LLMs (and our own children).

And it has an impact — even when we don’t know it.

Called a “neural network,” this mathematical system could learn tasks that engineers could never code into a machine on their own.

— Cade Metz, “Who Is Making Sure the A.I. Machines Aren’t Racist?” (March 15, 2021)

The answer to “who is making sure,” by the way, is “no one.” We’ve left alone the orphans in poisoned libraries. The result is predictable:

About six years ago, A.I. in a Google online photo service organized photos of Black people into a folder called “gorillas.” Four years ago, a researcher at a New York start-up noticed that the A.I. system she was working on was egregiously biased against Black people. Not long after, a Black researcher in Boston discovered that an A.I. system couldn’t identify her face — until she put on a white mask.

— Cade Metz, “Who Is Making Sure the A.I. Machines Aren’t Racist?” (March 15, 2021)

AI has claimed its inheritance.

Children, AI, and Learning

Large Language Models — LLMs — do not learn language in exactly the same way children do. Children acquire language through lived experience: trial and error, gesture and speech, social correction and emotional negotiation. LLMs, by contrast, are trained on massive static datasets — seas of words without living bodies behind them. In reality, they learn patterns, not meanings.

LLMs learn to predict continuations, not intentions. In that sense, they’re more like super-sized autocorrect programs than like anything human. (To be fair, there is more to it than just “autocorrect.”)

So when it comes to language itself, the analogy between children and LLMs falters. Children live their way into language; LLMs calculate their way through it.

But when we turn to culture, the analogy grows sharper. It helps us understand much about how bias, bigotry, and racism permeate the programs.

Children absorb the cultural environment they are born into — not by critical reasoning, but by exposure. They internalize assumptions about race, power, gender, and worth without ever being explicitly taught. They learn from what is praised, what is punished, what is left unspoken but universally enforced.

And so do LLMs.

When we train a model on the full sweep of human language —

with all its historical prejudices baked into law, medicine, journalism, and everyday discourse — we are not simply teaching it vocabulary. We are transmitting to it a map of human culture, with all its distortions intact.

LLMs do not understand this inheritance. They do not question it. They simply mirror it. They become fluent in the unspoken grammar of bias, just as surely as any child immersed in a poisoned cultural environment.

The difference is that with LLMs, the scale is larger, the speed is faster, and the reach is global.

And when the machines echo back our buried assumptions, they are not malfunctioning. They are doing exactly what they were built to do: learning from us.

The tragedy is not that they learn. The tragedy is what we have left behind for them to learn from. This is amplified when we turn LLMs loose to learn on their own, abandoning them like orphans in poisoned libraries. Especially when, because of our own “lived experience,” we may not even realize the library is poisoned, as when Clarifai tried to train content moderation systems with two databases: one with G-rated images that featured mostly white people and the other with pornography that featured mostly Black people.

“The data we use to train these systems matters,” Ms. Raji said. “We can’t just blindly pick our sources.”

This was obvious to her, but to the rest of the company it was not. Because the people choosing the training data were mostly white men, they didn’t realize their data was biased.

— Cade Metz, “Who Is Making Sure the A.I. Machines Aren’t Racist?” (March 15, 2021)

Prepping the Poisoned Library

This is a good point for me to deliver on my promise above to explain the scare quotes around “automatic” and “data.”

Machine Learning Isn’t Really (or Always) Automatic

First, “automatic” in the context of training AI systems is not 100% automatic. We choose the datasets on which AI systems are trained. Some are curated, cleaned, prepared; some are not. Nor is the learning process itself always automated. I’m no expert, but I know of at least two areas — HITL and RHLF — where humans insert themselves into the training.

HITL is Humans in the Loop and is a broader concept: humans may be involved in numerous different parts of the training — data labeling, model evaluation, or live system corrections. RHLF is Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback and is more specific, involving humans ranking or rating model outputs to reinforce preferred behaviors, and then reinforcement learning algorithms adjust the model’s responses based on those ratings.

Think of it like this: HITL is like having a coach on the field during practice, giving tips whenever needed; RLHF is like having a judge after the game, scoring every move to retrain the player for next time.

There’s No Such Thing as “Raw Data”

You may have guessed this already from all I’ve said above about the orphans in poisoned libraries, but there’s no such thing as raw data.

We often say, “The data speaks for itself” or assure others that “the data doesn’t lie.” The problem, as I think I showed above, is that the data doesn’t speak for itself: it speaks for us; it mirrors our prejudices and biases. And data can, indeed, lie.

This is because,

[h]ow data are construed, recorded, and collected is the result of human decisions — decisions about what exactly to measure, when and where to do so, and by what methods. Inevitably, what gets measured and recorded has an impact on the conclusions that are drawn.

— Nick Barrowman, Why Data Is Never Raw, 56 New Atlantis 129 (Summer/Fall 2018).

And as an example of how data, then, can lie, Barrowman offers this:

For example, rates of domestic violence were historically underestimated because these crimes were rarely documented. Polling data may miss people who are homeless or institutionalized, and if marginalized people are incompletely represented by opinion polls, the results may be skewed.

— Nick Barrowman, Why Data Is Never Raw, 56 New Atlantis 129 (Summer/Fall 2018).

To be fair, Barrowman doesn’t used the word “lie.” He instead points out that “all data is cooked” and it is the cooking that can, if we aren’t careful, result in untrue or wrong results. Or, as I said, “lies.”

And unlike what I’ve tried to do here, Barrowman didn’t even get into the way that language itself is cooked. There’s no such thing as “raw language,” either.

Surface Level Corrections and Covert Bias

Thus, it’s not just a problem of picking the right datasets for training. That might have helped with the content moderation system described above, but that’s not the chief method by which cultural attitudes are passed from generation to generation or, in our case, people to LLMs.

Culture is a way of life within a society that is learned by its members and passed down from generation to generation—language plays a central role in this process of cultural reproduction.

— Yan Tao , Olga Viberg , Ryan S Baker , René F Kizilcec, “Cultural bias and cultural alignment of large language models“ (September 17, 2024).

And if culture is passed through the bloodstream of language, then simply moderating what is said aloud — telling LLMs not to say certain things, or training them to prefer certain phrasings — is a surface-level fix at best. Just as it is sometimes for our children.

Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback can nudge models away from overtly biased outputs and it can teach them to adopt the forms of politeness we socially reward. But it cannot reach into the deeper structures that the models have already absorbed: the old hierarchies, the historical assumptions, the sedimented judgments that shaped the language in the first place.

Bias does not vanish because we tell a machine to be polite.

It hides. It becomes harder to see, harder to trace, but no less influential. The poisoned lessons remain — they simply wear nicer clothing.

We see the consequences already. Predictive policing systems claim to operate without racial data, yet disproportionately target Black and Brown communities because they inherit patterns of enforcement from historically biased crime records.

Facial recognition algorithms misidentify darker-skinned individuals at far higher rates, even when “diverse” datasets are used.

Computer scientist Joy Buolamwini was a graduate student at MIT when she made a startling discovery: The facial recognition software program she was working on couldn’t detect her dark skin; it only registered her presence when she put on a white mask.

— Tanya Mosley, “‘If you have a face, you have a place in the conversation about AI,’ expert says“ (November 28, 2023).

Content moderation systems, trained to prioritize “civility,” disproportionately silence marginalized voices because they mistake discomfort with disruption.

The machines do not intend this. They are simply learning what we have taught them to see, even when we no longer speak it — or allow them to speak it — aloud. (By the way, I already have plans for another blog post on how the arguments that “structural racism” is not real are bullshit, because racism is built in to the most basic of structures: the structure of our languages. And LLMs are the proof.)

Culture is not only explicit. It is implicit. And our machines, like our children, are always listening.

Language and Culture

Writing this article has already helped me see that there are at least two other articles I need to write. The problem is that I try to keep this blog focused on things relating to the Law. And some of what we’re talking about here with LLMs and AI generally get into other areas.

For example, the interaction of language and culture.

Language and culture are deeply intertwined, each shaping and sustaining the other.

Language is not just a tool for external communication but a vital part of culture itself, carrying shared beliefs, values, customs, and social structures across generations. While humans are biologically capable of acquiring language, it is through cultural immersion and social interaction that language and meaning develop.

Additionally, language transmits culture, and culture, in turn, influences how language evolves. As societies change, so do their languages, reflecting shifts in values, behaviors, and identities.

Learning a language thus inherently involves learning its cultural context, since meaning, communication styles, and even social mobility are bound to cultural frameworks. True linguistic competence, especially across cultures, requires cultural understanding, making language teaching inseparable from cultural teaching.

All of this explains why — at least to linguists, anthropologists, social scientists, and the rare deep-thinking psychologists — language infects LLMs (and other forms of AI) with racism. As I already said, racism is baked in to our language (however much some people might rail against the idea of structural racism).

Real World Consequences: Bias Beyond Theory

It’s easy to talk about bias in AI as if it were theoretical — something abstract and academic, safely removed from daily life. But bias is never abstract. It has real-world consequences, and they are disproportionately borne by the most vulnerable among us.

Predictive Policing: Bias Embedded in Algorithms

Consider predictive policing. At its core, predictive policing relies on algorithms analyzing historical crime data to forecast where crimes might occur next. It sounds neutral enough — except that historical crime data isn’t neutral. Policing in the United States has never been equally distributed; neighborhoods populated primarily by Black and Brown communities have always faced greater scrutiny, harsher enforcement, and higher surveillance.

When predictive policing algorithms learn from this historical data, they inherit and amplify these biases. Because they don’t measure crime; they measure enforcement.

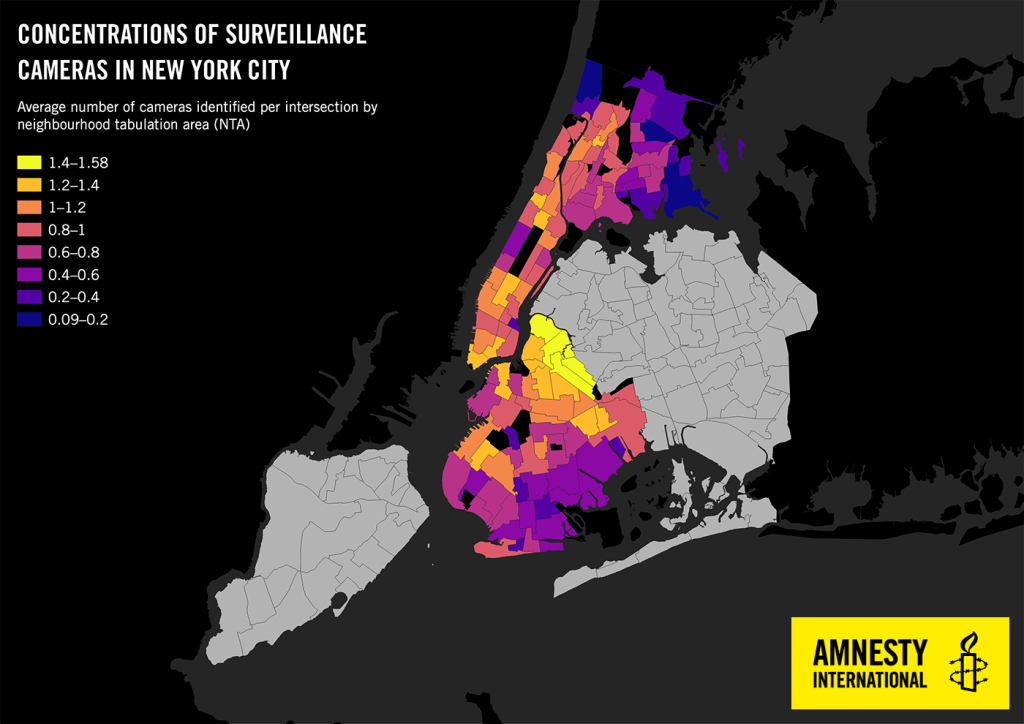

Thus, surveillance devices — Shotspotter microphones, license plate readers, CCTV cameras — aren’t distributed evenly. They’re densely clustered in communities of color.

Because the algorithm predicts crime where police have always looked hardest, the cycle continues.

Risk Assessment Tools: Automating Injustice

This bias isn’t confined to policing alone. Risk assessment tools like COMPAS, widely used in sentencing, parole, and bail decisions, similarly claim objectivity while reinforcing existing racial inequities. COMPAS analyzes various factors — criminal records, family backgrounds, employment status — to calculate a risk score intended to predict recidivism.

Yet these factors themselves are deeply entangled with race and class. Structural inequalities mean that Black defendants often score higher risks due to systemic disadvantages — less access to employment, education, and stable housing — factors influenced by generations of racism rather than individual criminal tendencies. In 2016, ProPublica famously exposed COMPAS as systematically rating Black defendants as higher risk than white defendants, even when controlling for other factors.

Automated Systems: Scaling Bias

The issue isn’t just bias — it’s scale. Automated systems replicate biases on an unprecedented scale, embedding them deep within institutional structures and bureaucracies. Algorithms used by social services, employment agencies, and even medical institutions inherit biases from the data fed to them, reinforcing racial disparities in every corner of public and private life.

Automated hiring systems routinely downgrade resumes with ethnic-sounding names. Medical algorithms underestimate the pain of Black patients. Mortgage approval algorithms systematically undervalue properties in minority neighborhoods.

AI Bias Destroys Lives

Sonia M. Gipson Rankin shows us: bias in AI is not theoretical — it ruins lives. People lose jobs, homes, and freedom because algorithms quietly encode prejudices beneath a veneer of mathematical objectivity. These are not merely errors or oversights; they represent real harm to real people, multiplying injustices under the cover of neutrality.

Bias in AI is an urgent, tangible crisis. If left unchecked, the poisoned libraries of today will keep harming generations of tomorrow.

Closing Reflection: Building Better Libraries

We left orphans alone — orphans in poisoned libraries. We gave them no guidance, no curation, and no warnings — only the implicit instruction to learn everything. And they did exactly as asked. Now, they mirror back the biases, the injustices, and the prejudices we’ve left behind and we either just ignore it, or feign shock and outrage.

But it is our responsibility to acknowledge the poison in the libraries themselves. We must recognize and confront this. I don’t have a carefully-thought-out plan for how to do that. But I think it starts by carefully curating, thoughtfully selecting, and continuously scrutinizing our datasets and cultural teachings.

We’re going to miss some stuff. After all, as I hope this post has made clear, this is truly the most structural of structural racism problems. It’s not just in what we think: it’s in how we talk about what we think. Racism shapes our language and language shapes our racism.

The only way to start to work on the problem of that infecting our AI systems is libraries at least nominally freer of poison, where learners can thrive without inheriting all our unchecked prejudices.

Until then, we should be very, very careful about where and how we use AI in predictive policing, risk assessment tools, and other carceral software.

This task is ours, urgent, and undeniable.

My Other Artificial Intelligence Articles

- Twenty-First Century Delphic Oracle – where I first introduced AI as a modern “oracle” and compared it to the Delphic Oracle of the Ancient Greeks.

- From Fumes to Function – where I explained how I do (and don’t) use AI in practice.

- Ghosts in the Machine — where I talk about why LLMs sometimes seem to be conscious.

The post Orphans in Poisoned Libraries appeared first on Fresno Criminal Lawyer. It was written by Rick.