As the Covington team discussed in a recent article, use of AI models in biopharma is on the rise, with use cases spanning the life cycle of drugs and biologics, including product development, manufacturing, and pharmacovigilance. Recently, FDA announced its own intentions to aggressively scale the use of AI in regulatory review and launched an internal AI tool for use by FDA regulatory personnel.

FDA is also reviewing comments on a draft guidance on AI in the drug life cycle (“Drug AI Draft Guidance”). The Drug AI Draft Guidance recommends a framework for assessing AI uses that inform decisions by FDA or actions by regulated industry to comply with regulatory requirements. Under this framework, a biopharma sponsor using AI may need to develop detailed documentation about the model for provision to FDA in an application or in an FDA inspection. The documentation might involve detailed information about the training or testing data used to develop the model, as well as the results of model performance assessments. FDA has not ruled out the potential that the Agency could, in some circumstances, require a sponsor to submit or provide access to the data used to develop a model, to support the Agency’s review.

Using AI in the drug life cycle raises important questions, including questions about deploying the AI in a way that complies with relevant regulatory requirements. One set of challenges is raised by the very common scenario where a sponsor uses an AI model developed by a different company, such as a tech partner or vendor. From a regulatory planning perspective, the model developer is a “third party” to the interactions between the sponsor and FDA (or regulatory bodies in other countries).

As FDA emphasizes in the Drug AI Draft Guidance, the biopharma sponsor is responsible for ensuring that necessary documentation and data about an AI model and its development are submitted in an application or available to FDA in an inspection. To develop this documentation and to conduct any needed performance evaluation of an AI model, the sponsor may need access to detailed information about the model and its development and, potentially, the ability to conduct additional testing of the model. However, it may be infeasible from a technology or commercial perspective for a third-party model developer to provide sufficient access to the biopharma sponsor, due to the proprietary nature of information about the model or other factors.

There is a potential solution, however, in the form of a mechanism that is often used to facilitate FDA review of proprietary third-party information in the context of drug applications: the drug master file (“DMF”).

What is a Drug Master File (“DMF”) or “Model” Master File (“MMF”)?

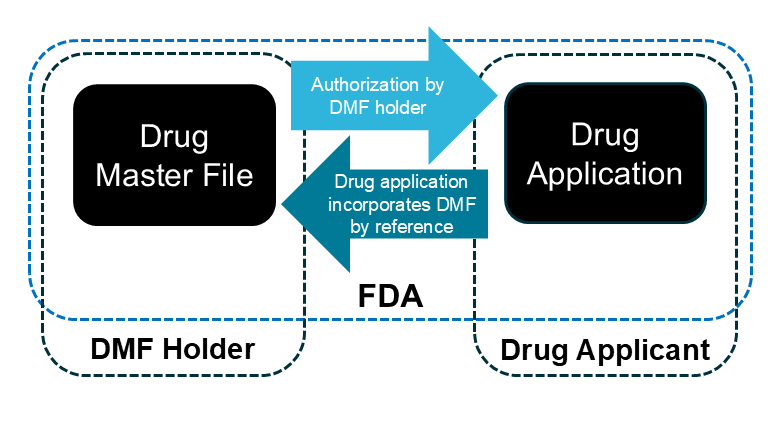

DMFs provide a mechanism for voluntary submission of confidential information to FDA outside of other formal avenues like marketing applications. DMFs often contain drug manufacturing information, but can also contain other types of information. The submitter, or DMF “holder,” can authorize another party — an applicant or sponsor — to incorporate information in the DMF by reference in one or more human or animal drug applications. Ordinarily, FDA only reviews the information in a DMF when the Agency reviews an application referencing the DMF. FDA regulations address various aspects of DMFs, including the availability for public disclosure of certain information in a DMF (e.g., 21 C.F.R. 314.420).

In January 2025, FDA published a notice in the Federal Register regarding the use of one type of DMF (the “Type V” DMF) for confidential submission of “model” master files (MMFs) — DMFs that contain “a set of information and data on an in silico quantitative model or modeling platform supported by sufficient [verification and validation]”. This notice focused on a particular category of computational use cases: in silico models and simulations to be leveraged by generic drug applicants.

It’s important to note that the January 2025 Federal Register notice does not use the term “artificial intelligence.” However, there is at least some conceptual overlap between the types of models discussed in the notice and those discussed in FDA’s Drug AI Draft Guidance (e.g., predictive modeling for clinical pharmacokinetics). Clarification from FDA about its use of “AI,” “model,” and related terms will be helpful as the Agency develops policy in this area.

In March 2025, FDA hosted a webinar to discuss the Agency’s thinking on the submission and use of MMFs to support marketing applications, the video recording for which was recently made available. Like the January Federal Register notice, FDA’s webinar focused on the potential of MMFs to support generic drug applications. According to the webinar, model developers seeking to open MMFs may request FDA input and pre-submission support.

Establishing an MMF

In the March 2025 webinar, FDA emphasized that while the Agency does not formally approve or reject MMF submissions, a prospective Type V DMF holder must obtain FDA’s permission for their submission to be accepted. Additional information about letters of intent for Type V DMFs is provided in FDA regulations and in an FDA draft guidance. According to the draft guidance, the letter of intent should include, among other items, the specific information to be included in the DMF and why the information could not be submitted in an application (i.e., why the information is confidential).

Strategic Considerations and Outstanding Questions

There are a variety of outstanding questions and strategic regulatory considerations for AI developers or sponsors who are considering the use of a model master file.

- Public listing of DMFs and other disclosure considerations. Prospective DMF holders will want to take note of the public availability of certain information contained in DMFs. FDA publishes a quarterly list of DMFs and, as with other types of submissions to FDA, the disclosure of information in a DMF is governed by FDA regulations.

- Could MMFs have utility for a broader set of models and use cases than FDA has spoken about publicly? As noted above, FDA’s January 2025 notice and March 2025 webinar focused on MMFs to support the use of quantitative models or modeling platforms in generic drug applications. What about MMFs outside of generic drug development and for a broader variety of computational tools than FDA described in its recent webinar? We’re not aware that FDA has spoken publicly to this issue, but MMFs presumably could have an important role in the deployment of models to support other types of drug applications and in other parts of the drug life cycle. In general, FDA has not provided detailed considerations for third-party AI models in the drug life cycle.

- What about uses of AI for regulated activities that are not described in a drug marketing application, such as some pharmacovigilance uses of AI? Pharmacovigilance is one area where AI has many promising use cases. As FDA notes in the Drug AI Draft Guidance, certain pharmacovigilance documentation (e.g., documentation of processes and procedures) generally is not submitted to FDA. Rather, it is maintained by the sponsor and made available to FDA during an inspection. Thus, when an AI model is used in pharmacovigilance, information to support the use of the model may be reviewed by FDA during an inspection rather than in an application. In this context, if the AI model is developed by a third party, could an MMF facilitate access by FDA to the relevant AI model documentation?

We expect these and many other questions to be increasingly important as AI developers and biopharma sponsors work together to deploy new AI tools in the drug life cycle.