Reading Time: 8 minutes

I had a sales pitch from a program inside Elsevier’s SSRN unit. The idea was to create a Research Paper Series that showcases the law school’s scholarship. The Dean pitched the cold call over to me and so I followed up. I was interested to see that part of the pitch relied on Cloudflare firewalling scrapers. My experience to date with their other product (BePress and Digital Commons) is that they are not inhibiting scraping so it was interesting to me that they might be investing in the resources for their own platform.

I’ll be frank, I’m not clear on who in the legal profession use SSRN outside of the academics putting their work there. In addition to being a place to share work, part of the SSRN pitch is that it appears in web search results. I am not a huge fan of anecdata but I have never come across an SSRN piece using web search, so I’m wondering if that is reflective of all SSRN content, not just legal. It also sounds like search engine optimization (SEO) bafflegab that I’m not sure can be validated. In fact, this was my problem with the overall pitch.

Optimizing for Automatons

Speaking of bafflegab: I had to laugh at this recent story about SEO in the age of artificial intelligence. Now we’re chasing GEO (or AEO, as the author also calls it) to make our sites more accessible to crawlers and scrapers. Not necessarily to improve our placement in search but to have our content ingested for training. It is the concept of a plan to be included in a search result, not to actually be part of a search engine results page (SERP).

Or, as another author on Fast Company put it:

If SEO’s past is any teacher, we’re headed toward a new playground of snake oil and shortcuts. Soon you’ll see “GEO specialists,” “AI optimization gurus,” and “zero-click quantum marketing” workshops popping up. Brands will chase algorithms that nobody fully understands, pay for tools that promise to “place you inside the answer box,” and invest in techniques whose mechanics are opaque even to those selling them.

Why you don’t need a magic GEO hack, Enrique Dans, Fast Company, October 29, 2025.

Long-time readers may remember that this was one expectation I had. Not that I anticipated the dumbness of “GEO” as an acronym, but that authentic law library content could be ingested and presented to AI chat users. As that author describes, what you need is to have good, authentic content that displays accurate information and expertise. Chasing SEO and GEO and AEO and whatever comes next is a resource sink, not an investment.

I’ll return to the SSRN pitch in a moment. But one piece that caught my attention was that Elsevier uses Cloudflare as a web application firewall (WAF) to reduce scraping. I had asked why our law school would want to pay for a dedicated resource to generate analytics that were soft. When I say “soft”, I mean that a download is not a view by a human, which (I think?) is our goal. If we are looking to measure engagement, we want there to be a person at the other end who may read, share, or even respond to or build on scholarship.

I’m very skeptical of the visually appealing downloading visuals from Elsevier’s BePress-based Digital Commons platform. I mean, this is a lot of legal scholarship being downloaded for a three-minute window on a Saturday morning. (the video is at 10x speed) It is noticeable to me that the download counter at the top of the page does not seem to reflect these downloads. You can refresh the page after seeing a couple hundred downloads and the top level number doesn’t change. This may just be eye candy (and, if so, what is the purpose and what is the Elsevier strategy for publishing it).

I expect it reflects a large amount of scraping. I mean, people have already published ways of grabbing BePress content for preservation purposes. We expose our content in a variety of ways, in particular using website XML sitemaps, that can make scraping simpler by broadcasting what URIs resources are using. It is one reason I do not take my own analytics too seriously and I squint at any “views and visitors” data from any organization that measures success that way.

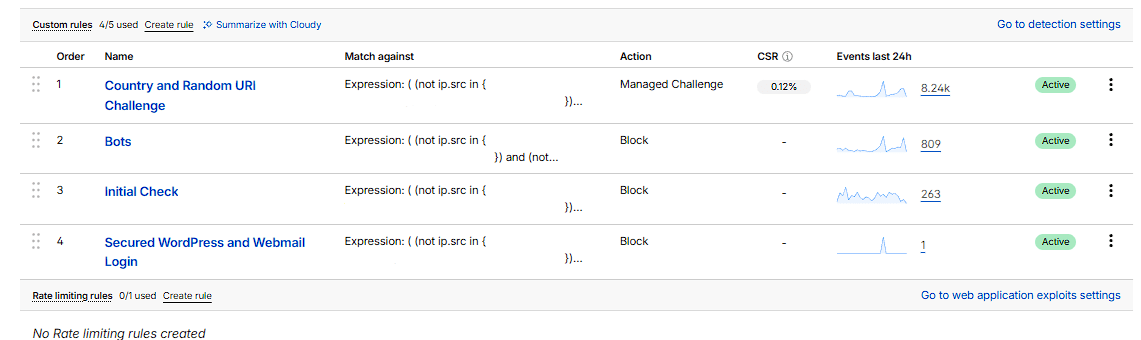

For me, it’s a tension between making information accessible and maintaining my ability to afford resources. I have had two blog readers reach out to let me know that my own fine-tuning of the Cloudflare WAF has blocked them out. In both cases, it was because they used a network provider who had come up in my analytics as a potential scraper. This made me tailor my rules a bit, so that now most visitors who are coming in from questionable sources or accessing questionable resources will be prompted with a managed challenge.

They are now working much better as a funnel, with the managed challenge working to block scrapers without blocking legitimate visitors. A human should always be able to move through that verification step. As you can see, I had over 8000 blocks in the past 24 hours on that chart for visitors with questionable starting points or seeking questionable endpoints. This includes any visitor who is trying to recall all posts under a given category or metadata tag. This is a red flag because it’s not normal behavior for my sites. Also, as an English-language blog, it’s rare to have visitors from outside the English-speaking world.

This means that, even before I invoke my more specific bot rules, I’ve caught most of the exploitative activity. The bot rule captures another 10%, and then my hyper focused block rule captures another 3% or so. Since most of the bad actors are caught in the previous rules, most of the attempts to access my administrative interface are also blocked. Only one managed to get through to the final rule that is designed specifically for that purpose.

Cite Me!

I have to say I find a lot of the metrics and alt-metrics positioning in legal scholarship to be a bit … off. The idea of a branded university scholarship page seems seems off to me, especially for a single college like a law school. It feels like a corporate or commercial concept (like a branded LinkedIn page) transposed onto a publishing platform. The difference is that scholarly publishing is already inside baseball and does not offer a potential new market.

My own experience is that legal scholarship is not something that is commonly used outside of academia (see also this 2011 piece), so it feels as though a research paper series would be mostly preaching to the amen corner. There’s also the question of whether scholarship is used “just in time” or “just in case”. Since the research paper series product seems to be about better finding (assuming it’s not just about branded presentation), it would depend upon there being an audience seeking it out.

If the former, then we can rely on existing platform and web search to retrieve an article or develop our search approach from that angle; SSRN is just a potential source, not a destination. I think the latter—where researchers are trying to read everything published on a topic as it emerges—is probably going to include a small number of similarly situated authors working in the same area, and they may already have following tools or habits. Even if SSRN is used for works-in-progress (WIPs), that would seem to lean harder on the insider use of the information, since no one is going to cite a partially baked article.

There is a blog post on court-citation of legal scholarship from last month that I won’t link to because of the platform that hosts it. It looks at “top” scholars. I mean, that seems precious. Also, practically speaking, most scholars are not “top” scholars so how does this even help assess overall trends in legal scholarship and citation by courts?

What are reasonable methods for me to verify that the value placed into the research paper series is leading to measurable outputs (like increased authoritative citations, etc.)? Elsevier suggests the advantage of having Elsevier PlumX Metrics but that doesn’t connect to HeinOnline so it makes me wonder how much journal-to-journal citation is captured. One benefit of being on their BePress platform is that PlumX tie-in, I suppose. I also have a lot of questions about how the citation matching happens, although perhaps my bigger question is who it really matters to.

I’m really curious about PlumX’s curated blog list and how they do URL link matching to confirm a citation is correct (especially when someone like me links to permanent URLs that are not on a publisher site). It looks like they had a partnership with an academic blog aggregator in 2016 when Plum belonged to EBSCO but I can’t find any trace of this group any longer. Maybe Elsevier absorbed the aggregator. I LOVE this page that has to be AI-generated and hosted by a company that purports to be from “Mariliefurt, 98009 Oregon”, particularly its citation of SSRN data about why open access leads to higher citations, which echoes what the SSRN sales rep told me. It would not surprise me, based on my recent reading of scholarly articles to believe that 10% to 15% of citations are people citing themselves. But I’d want a more reliable source!

The question I didn’t pose to SSRN was why we would want to license a branded platform on SSRN when we were already paying them well for our hosted Elsevier BePress branded platform. Why aren’t the network effects they offer already present in their BePress platform? And, if they aren’t there, why wouldn’t we want to cancel our BePress repository license and just post everything to SSRN, collect our minted DOIs, our higher purported click-through rates, and be done with it? This may be come to pass anyway, since our university has a campus-wide repository that the law school repository overlaps.

The answer seems to me to be that SSRN is a front-end resource, not a long-term resource (although, by populating it, authors are helping Elsevier build a commercial product, just as lawyers are doing with the docket harvesting sites). A given piece of legal scholarship probably has a short life-cycle in most cases. It looks at a current issue that ages out or it adds to a strata and is then superseded by subsequent strata.

SSRN may be able to help legal scholars find homes for new scholarship, especially if they’re posting works in progress, or help expose a published article. But that takes me back to the insiders: anyone interested in a topic and area of research is probably aware how to browse the existing e-journals and, if they belong to a law school like ours that has an organization subscription, can subscribe to as many e-journals as they like. A law school-specific research paper series seems destined for a niche audience (probably ourselves?). The paper series subscriber numbers the SSRN rep shared with me suggested this is true. I mean, surely scholars in an area are already following each other or know how to?

I have appreciated this journal article by Michelle Knapp and Rob Willey (sorry, a blog link by me doesn’t help towards citation count!) and I think it’s useful for folks who need to invest time in SSRN. I do wonder whether the analytics, if repeated now, would lead to the same impressions. 2023 was probably the higher water mark for web search engines, given the outflow of generative AI and its impact on search outcomes, and I’m not sure that SEO functions the same way any longer.

As I was talking to the SSRN rep, they offered up the benefits that the Elsevier platform could offer for amplification. They would promote the research paper series to common social media platforms. But I’m very conflicted about providing content, even through a third party, to places like X, and Y, and Z. There is also the question of what audience is on any given platform any longer. I really appreciated this survey by a Dutch publisher into the fragmentation of discourse by scholars (survey). Not just because it looks at an issue that I’m curious about, but also because publishers should be adapting.

One of the takeaways from this survey was that, for some communities, a lot of activity, but not discourse, has moved on to Microsoft LinkedIn. I don’t know how social media fragmentation has impacted legal scholarship, but I would expect amplification for this work to face the same challenges. Social media reach isn’t what it used to be and, when it comes to legal scholarship and the insiders who consume it, I’m not sure more social media amplification leads to measurable outcomes.

I think any centralization on Microsoft LinkedIn is a terrible outcome but it was still interesting to know. These researchers are now splitting their social interactions with their other networking activities. I think a curious person could find it all but it could mean maintaining more profiles. On walled gardens like LinkedIn, FOMO might cause someone to maintain a profile, even if it was otherwise not creating value for them.

I can’t see the operational value of having a publisher promote legal scholarship to places like Facebook, Instagram, X, or even LinkedIn. The audience amplification is likely to be generic; I have not seen data to suggest that legal scholarship amplification into these platforms leads to conversions that result in citation or access. It also calls into question how to balance that paid marketing with any strategic marketing the law school is already engaged in. It risk not being a force multiplier but a competing or duplicative effort.

It feels a lot like clout chasing. Or, for the olds, Klout-chasing. I kept returning to what the value was for the law school. Like the search engine optimization consultants, some of whom still email me to tell me my website is not performing well on SERPS, it is a lot of non-causal possibilities. First, tell me why my personal non-monetized blog needs to appear higher on a SERP. Then, I might care.

Show me the linkage. If we publish a document to your platform, it has this network effect. It increases its likelihood of being read by X over using your OTHER product. That likelihood translates into it being cited Y times more than it otherwise would have. Those citations translate into (a) more prestige for the author or university (ooooh, would we be “top” then!?!?), (b) more grant funding for the author or university, etc. Not just the possibility of but we have measured and this is actually what outcomes are. If you can’t show me how my $6,500 payment for 25 articles a year (on a site where we can currently upload our publications for free) is going to convert back into a value greater than or equal to that $6,500, I am really not interested.

But even more than that, I would want to know that the metrics are accurate. I just don’t think we live in a place where web analytics are as reliable any longer. That’s the foundation on which any metrics-based investment needs to build. In the age of artificial intelligence-infused search and retrieval, I would expect to see more specificity in what a publisher can and what they know they can’t do.